NewFest’s 37th Annual New York LGBTQ+ Film Festival - 2025

The 37th Annual NewFest ran from October 9th-21st. So many AMAZING films. Check out reviews of what I was able to catch below!!!

Selected Feature Films

Blue Film

⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

Blue Moon

⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

Christy

⭐️⭐️⭐️

The Chronology of Water

⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

Four Mothers

⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

In Transit

⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

Love Letters

⭐️⭐️⭐️

A Night Like This

⭐️⭐️⭐️

Night Stage

⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

Only Good Things

⭐️⭐️⭐️

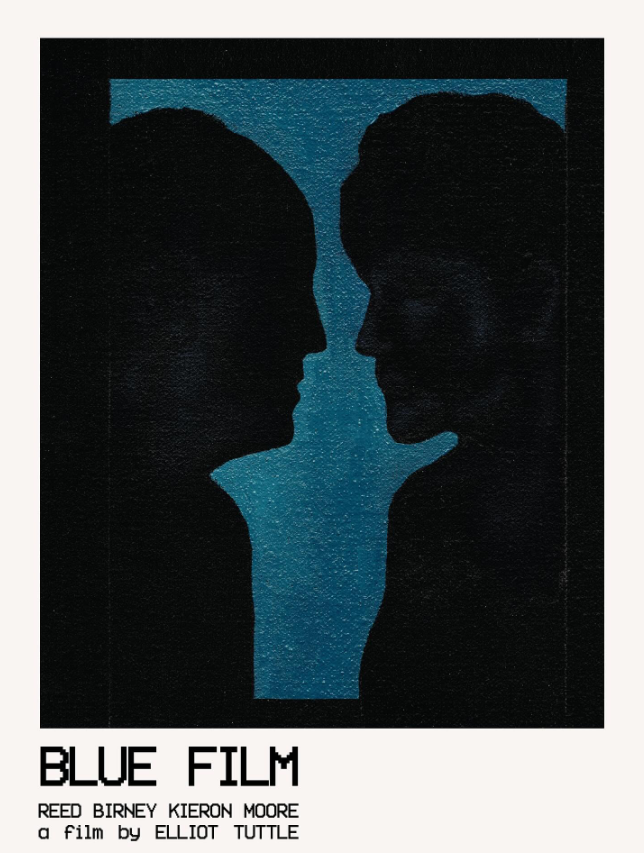

Blue Film

⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

Feature Film

Film Production Companies: Fusion Entertainment

Rating: NR / Run Time: 82 minutes

Language: English

Director: Elliot Tuttle

Writer: Elliot Tuttle

Starring: Reed Birney and Kieron Moore

“In order for this to work, you have to do what I say.”

Aaron Eagle (Moore) is a Los Angeles–based queer camboy who seems to take pleasure in degrading his followers. Using homophobic slurs as entertainment, he gives his clients exactly what they want — as long as they pay the price. One day, Aaron announces on his stream that he’s agreed to spend the night with one of his clients for $50,000. Watching from the other end of the screen is a ski-masked man, fixated on Aaron’s every move.

When Aaron arrives at the client’s home, he’s greeted by the masked man, who introduces himself as Hank (Birney). Aaron assumes they’ll get straight to business, but Hank has other plans. Refusing to remove his mask, Hank begins interviewing Aaron on camera, starting with small talk that quickly turns invasive. As the questions become more personal, Aaron grows frustrated and prepares to leave — until Hank calls him by another name: Alex.

It’s then we realize this is no random encounter. The two share a deeply unsettling history. Years earlier, Hank was arrested for the alleged sexual assault of one of Aaron’s high school classmates. Hank, it turns out, was Alex’s English teacher. He claims nothing happened with that student and insists he never acted on his attraction to Alex — a statement that complicates the power dynamics and moral ambiguity that now define their reunion.

From here, the film becomes a tense psychological dance. What begins as a transactional meeting evolves into a fraught night of confession, manipulation, and blurred boundaries. Both men are broken in their own ways, shaped by the choices and traumas that have led them here. As the night unfolds, the film drifts into dangerous territory — one particular role-playing sequence evokes both desire and revulsion in equal measure, testing how far each man is willing to go.

Writer/director Elliott Tuttle walks a daring tightrope, asking the audience to empathize with two deeply flawed individuals. It’s an uncomfortable proposition — particularly given Hank’s past — but it’s also what gives Blue Film its emotional charge. The film’s exploration of perversity, guilt, and spirituality offers a fascinating, if at times disquieting, portrait of people wrestling with their own contradictions.

Shot largely within the confines of a rented Airbnb, the film’s claustrophobic tension is skillfully amplified by Ryan Jackson-Healy’s cinematography and Isaac Eiger’s restrained, pulsing score. Both Moore and Birney deliver fearless performances, grounding their characters in raw vulnerability even as the story pushes into uncomfortable spaces.

All in all, Blue Film lingers in the gray areas between desire and danger and will leave you questioning everything long after the credits roll.

Review by Cinephile Mike

Blue Moon

⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

Feature Film

Film Production Companies: Sony Pictures Classics, Renovo Media Group,

Detour Pictures, Wild Atlantic Pictures and Cinetic Media

Rating: R / Run Time: 100 minutes

Language: English

Director: Richard Linklater

Writer: Robert Kaplow|

Starring: Ethan Hawke, Margaret Qualley, Bobby Cannavale, Jonah Lees,

Patrick Kennedy, Simon Delaney and Andrew Scott

“Who wants inoffensive art?”

It’s March 31, 1943, and the wind is sweeping down the plain as Oklahoma! opens on Broadway at the St. James Theatre. Lorenz Hart (an absolutely outstanding Ethan Hawke) slips out before the final curtain and makes his way to Sardi’s for a drink — and maybe a little sympathy — from his friend, bartender Eddie (Bobby Cannavale). He’s feeling blue: the show marks the first collaboration between his longtime writing partner Richard Rodgers (a subtle and welcome Scott) and Oscar Hammerstein II (Delaney), signaling the end of one of Broadway’s most beloved partnerships. Together, Rodgers and Hart gave audiences The Girl Friend, The Boys from Syracuse, A Connecticut Yankee, and Babes in Arms, but Hart’s personal struggles have finally pushed Rodgers to move on.

At Sardi’s, Hart airs his frustrations to Eddie and to Morty (Lees), a charming soldier on leave and the pianist for the night, whom Hart affectionately nicknames “Knuckles.” He’s also expecting the arrival of his new muse and love, Elizabeth Weiland (a charming though underused Margaret Qualley). But this being Sardi’s — the unofficial heart of the Great White Way — it’s not long before Rodgers, Hammerstein, and the rest of the Oklahoma! team pour in to celebrate Opening Night, nervously awaiting the all-important New York Times review. Amid the crowd, tensions rise and old wounds reopen. We see Hart and Rodgers’ strained but tender exchange, moments of vulnerability between Hart and Elizabeth, and even a witty encounter with fellow patron E.B. White (Kennedy), which playfully hints at the origins of a beloved children’s classic about small friends with big hearts.

Unfolding in real time — a structure Richard Linklater has long mastered, most notably in Before Sunset — Blue Moon is a talky but intimate chamber piece that gives Hawke room to shine as the diminutive yet larger-than-life Hart. Through clever use of forced perspective, cinematographer Shane F. Kelly subtly reminds us of Hart’s small stature without diminishing his presence. Even in moments of heartbreak, as Hart realizes Rodgers will thrive with Hammerstein, Hawke imbues him with such warmth and wit that he never feels like a tragic figure. He may be down, but this Hart, pardon the pun, still has heart.

Based on letters between Hart and Weiland, Kaplow’s screenplay captures both the humor and the melancholy of creative separation, weaving sharp, literate dialogue that lets laughter sneak in amid the sorrow — much like a great musical number that turns pain into melody.

If the film falters, it’s in trying to juggle two competing stories — the dissolution of Rodgers and Hart’s partnership and the romance between Hart and Weiland. Both are compelling, but neither gets quite enough time to resonate fully. The more engaging thread is unquestionably the creative breakup, which leaves you wanting a bit more. Still, Qualley and Scott make strong impressions, radiating old-Hollywood magnetism even in their brief screen time.

Linklater’s film, though modest in scale, finds its rhythm in nostalgia and performance. All in all, outstanding performances and a touch of bittersweet sentiment will have you feeling all the feels as Blue Moon plays its final tender notes.

Review by Cinephile Mike

Christy

⭐️⭐️⭐️

Feature Film

Film Production Companies: Black Bear, Anonymous Content,

Votiv Films, Fifty-Fifty Films and Yoki

Rating: R / Run Time: 135 minutes

Language: English

Director: David Michôd

Writer(s): Mirrah Foulkes, Katherine Fugate and David Michôd

Starring: Sydney Sweeney, Ben Foster, Merritt Wever, Ethan Embry,

Coleman Pedigo, Jess Gabor, Katy O’Brian and Chad Coleman

“Do you know how easy it is to make people dislike you?”

Christy chronicles the life of the Coal Miner’s Daughter — no, not Loretta Lynn, but Christy Martin née Salters (an outstanding Sweeney) — the famed female boxer who became the first woman professionally signed by Don King (a delightful Coleman). The film traces her rise from winning the Toughman Competition in West Virginia in 1989 to her fateful return to the sport in 2010, following a tumultuous period that’s best discovered without spoilers for those unfamiliar with her true story.

In her early years, Christy struggles with the lack of acceptance from her parents Joyce (Wever) and Johnny (Embry) regarding her “lifestyle,” which she’s trying to make work with her “friend” Rosie (Gabor). While her parents believe the church can “fix” her, they remain supportive of her boxing career, traveling to ensure she gets proper training. After a key victory, Christy is approached by promoter Larry Carrier (Bill Kelly), who connects her with trainer Jim Martin (Foster). Initially reluctant, Jim ultimately takes her on — and soon convinces her that marrying him will be good for both her career and stability. When Rosie leaves her, Christy gives in, hoping this partnership will secure her success.

Sporting her signature pink and white gear, Christy quickly climbs the ranks of women’s boxing, eventually signing with Don King in Las Vegas. Her career takes off, though her ego occasionally alienates those around her. As the film follows her through her major bouts — including with Deirdre Gogarty (Stephanie Baur), Lisa Holewyne (O’Brian), and Laila Ali (Naomi Graham) — it also peels back the layers of a woman trapped between her public persona and private truth. Her volatile marriage to Jim grows increasingly suffocating, and the support she craves from her parents never comes. Everything builds toward that fateful night in 2010 that forever changed her life.

At its core, Christy is another sports biopic about overcoming adversity. While inspiring, it occasionally falls into familiar genre beats — a “been there, done that” retelling that feels a bit too polished for such a raw story. Christy Martin’s real-life journey is remarkable, but one can’t help feeling it might have been better served as a documentary rather than a glossy biopic built around expected emotional cues.

Still, the film’s watchability rests squarely on Sweeney’s powerhouse performance. She fully disappears into the role, radiating Christy’s grit, determination, and fragility. Each punch lands — both physical and emotional. Foster proves a fitting counterpart as Jim, crafting an unnervingly charismatic sociopath who makes your skin crawl. Wever and Embry make the most of limited screen time, with Wever in particular finding quiet moments of conflict and contradiction that linger.

Cinematographer Germain McMicking captures the fights with visceral immediacy — you feel every jab and hook — while editor Matt Villa assembles it all with kinetic rhythm. Yet between bouts, the narrative occasionally drags, weighed down by biopic conventions and predictable pacing. Director David Michôd, who showed such grit and urgency in 2010’s Animal Kingdom, seems constrained here by the genre’s formula.

All in all, Sydney Sweeney’s knockout performance keeps Christy in the fight, but you can’t help feeling that its subject deserves a film just as fearless as she was.

Review by Cinephile Mike

Screened at the 26th Annual Woodstock Film Festival (October 2025).

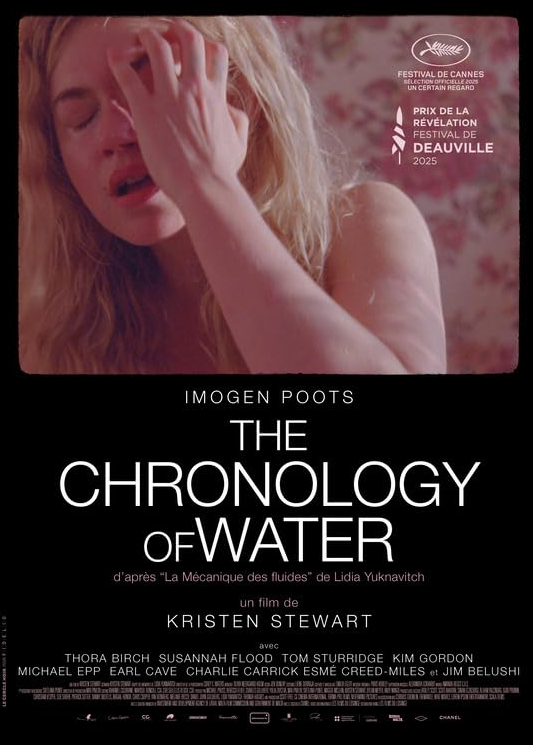

The Chronology of Water

⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

Feature Film

Film Production Companies: Scott Free Productions, CG Cinéma,

Telekompanija Forma Pro, NeverMind Productions, Fremantle,

Curious Gremlin, Lorem Ipsum Corp. and Scala Films

Rating: NR / Run Time: 128 minutes

Language: English

Director: Kristen Stewart

Writer(s): Kristen Stewart and Andy Mingo

based on the memoir by Lidia Yuknavitch

Starring: Imogen Poots, Thora Birch, Susannah Flood, Michael Epp,

Tom Sturridge and Jim Belushi

“All I was, was my body bleeding.”

Lidia Yuknavitch (played as a child by Anna Wittowsky and later by Imogen Poots) grows up in an abusive household that leaves her nearly mute. Her only escapes are the written word and the water. Whether she’s swimming or journaling her thoughts, both serve as ways to make sense of a world that has given her little love or stability. Her parents, Dorothy (Flood) and Mike (Epp), are incapable of offering the support she needs, and though the film hints at the darker truths of her childhood, it wisely keeps them offscreen. Lidia’s older sister, Claudia (Marlena Sniega as a teen, Birch as an adult), becomes her protector until she finally flees home, leaving Lidia to face the wreckage alone. When Lidia earns partial college swimming scholarships, her father tears them up in a fit of control — until she finally secures a full ride to a community college in Texas and makes her long-awaited escape.

But freedom doesn’t bring peace. Haunted by trauma, Lidia drifts between self-destruction and self-discovery, numbing her pain with alcohol and fleeting sexual encounters. She finds temporary solace in Devin (Sturridge), a folk singer who offers her a glimpse of stability — though their relationship, much like her past, is turbulent and raw. After failing out of college, she stumbles into a writing course led by One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest author Ken Kesey (Belushi), where her creative voice begins to emerge. It’s here that she starts to see a path forward — not away from her pain, but through it.

Told in a nonlinear format, The Chronology of Water captures the chaos and resilience of a woman fighting to define herself. As Lidia, Poots delivers a career-best performance — fierce, fearless, and utterly magnetic. She inhabits the role with such intensity that you can almost feel her gaze breaking through the screen, demanding to be heard. Every flicker of emotion reads as lived-in and real, making it impossible to look away. While the supporting cast makes strong impressions — particularly Belushi in a tender late-film scene — this is Poots’ film through and through, and she deserves to be in the Best Actress conversation for it.

In her feature directorial debut, Kristen Stewart proves remarkably assured. Co-writing the script, she structures the story in five distinct parts, collaborating with cinematographer Corey C. Waters to create a visual language that mirrors Lidia’s instability. Shot on 16mm with soft focus and blurred edges, the film often resembles an old home movie, its imperfect texture reflecting the fragmented memories at its core. Stewart approaches themes of abuse, addiction, and domestic violence with great care — never exploitative, always empathetic. She doesn’t ask us to excuse Lidia’s choices, but to understand the courage it takes to survive them.

Though its nonlinear structure can occasionally feel disjointed, that roughness feels deliberate — like the rhythm of crashing waves, pulling us under and pushing us back toward the surface. Stewart’s control behind the camera and Poots’ unflinching performance combine into something raw, haunting, and ultimately redemptive. All in all, Stewart proves as powerful a director as she is a performer, and in Poots, she’s found a muse who fully embodies her vision — a star reborn in the depths of the water.

Review by Cinephile Mike

Four Mothers

⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

Feature Film

Film Production Companies: Fís Éireann (Screen Ireland), The Common

Humanity Arts Trust (CHAT), MK2, Coimisiún na Meán, Raidió Teilifís

Éireann (RTÉ), Port Pictures and Portobello Productions

Rating: NR / Run Time: 89 minutes

Language: English

Director: Darren Thornton

Writer(s): Colin Thornton, Darren Thornton inspired by Pranzo Di Ferragosto

(Mid-August Lunch) written by Gianni Di Gregirio Simone Riccardini

Starring: James McArdle, Fionnula Flanagan, Stella McCusker, Paddy Glynn,

Gaetan Garcia with Niamh Cusack and Dearbhla Molloy

“You need to focus on what’s important now.”

Edward (an excellent McArdle) is an up-and-coming Irish writer whose debut queer coming-of-age novel has generated serious buzz. Invited to the United States for a book tour, he should be celebrating, but anxiety and self-doubt weigh him down. He’s far more articulate on the page than in person — and that’s not even his biggest challenge. His widowed mother, Alma (a delightful, dialogue-free performance by Flanagan), has suffered a stroke and now communicates solely through an iPad audio app. Edward is her primary caregiver, aided by home health aide — and former partner — Raf (Garcia). As Raf prepares to marry and move away with his new partner, Edward faces the daunting prospect of being left alone to care for Alma. He vents to his long-suffering therapist and friend Dermot (Rory O’Neill), and to his best mates Colm (Gearoid Farrelly) and Billy (Gordon Hickey), who can relate — they, too, are middle-aged men living at home as full-time caregivers to their mothers.

Determined to find a solution so he can attend his book tour, Edward starts exploring care options for Alma. But chaos arrives uninvited: Colm and Billy, at their breaking points, decide to escape to Maspalomas Pride, leaving Edward a voicemail — and their mothers, Jean (Molloy) and Maude (McCusker), in his care. Before he can catch his breath, Dermot joins the fun by dropping off his own mother, Rosie (Glynn), to free himself for the festivities. Suddenly, Edward is juggling four elderly women in one house — each with her own quirks, needs, and unfiltered opinions — while his own mother watches the madness unfold from her wheelchair. With no room left inside, Edward ends up sleeping in his car, and the comedy of errors begins.

The weekend spirals into glorious chaos: medical appointments, hair appointments, funerals, dietary restrictions, and endless phone calls from his manager and agent about the book tour he’s now missing. Raf tries to help, but his presence only complicates things further — the unresolved feelings between him and Edward simmer beneath every exchange. As tensions and tenderness collide, the story culminates in a road trip to Galway, where the four mothers seek out famed medium Maura (Cusack) for a bit of spiritual guidance — and, perhaps, some long-overdue healing.

The Thornton Brothers strike an impressive balance between heartfelt emotion and sharp comedy. Four Mothers unfolds like a well-tuned sitcom — quick, warm, and filled with genuine affection — yet it never loses sight of the emotional core: a son torn between obligation and selfhood. While the setup risks leaning into familiar stereotypes about middle-aged men and their mothers, the brothers’ script keeps things grounded, avoiding caricature through witty dialogue and a deep sense of empathy. McArdle anchors the film beautifully, playing Edward as frazzled yet sincere — his frustrations relatable, his affection palpable. Flanagan, as Alma, delivers deadpan brilliance, her iPad-generated barbs landing with perfect comedic rhythm. The ensemble of mothers shines throughout, especially in their group scenes — their stories, full of humor and heartache, speak to universal themes of love, aging, and letting go.

In their sophomore feature, the Thornton Brothers demonstrate a deft hand at blending comedy and pathos, crafting a warm and finely observed slice of life that deserves far more attention than it’s likely to get. All in all, Four Mothers delights in all its honesty and heart, reminding you to laugh through the chaos — and maybe pick up the phone and call your mother.

Review by Cinephile Mike

In Transit

⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

Feature Film

Film Production Companies: BKE Productions, Little Language Films

and Valmora Productions

Rating: NR / Run Time: 82

Language: English

Director: Jaclyn Bethany

Writer: Alex Sarrigeorgiou

Starring: Alex Sarrigeorgiou, François Arnaud, Theodore Bouloukos

and Jennifer Ehle

“It’s interesting, your job. You get to observe people so intimately, and watch them go about their lives every night.”

Lucy (Sarrigeorgiou) is mostly content with her life in Maine. Working behind the bar once co-owned and built by her late father, she’s a fixture in the small community. She lives with her boyfriend, talented chef Tom (Arnaud), and life is… good. Not great, but good. Then, things begin to shift. The bar’s co-owner Garry (Bouloukos) announces that he’s decided to sell—he needs to move on, care for his family, and feels the time is right. Lucy and Tom decide they’ll try to buy the bar, but Garry needs time to think about it. Doing so, however, will require a significant amount of money.

Enter Ilse (Ehle), an artist who has lived all over the world but now finds herself creatively blocked. Through a colleague, she comes to stay in a small, future artist residency in town. She frequents the bar, soaking in the atmosphere—and, in doing so, takes notice of Lucy. One night, while sketching her, the two strike up a conversation. Through a bit of negotiation, Ilse offers Lucy $25 an hour to pose for her, captivated by Lucy’s natural poses. Lucy agrees, seeing an opportunity to bring in extra funds, but chooses not to tell Tom—at least not at first.

As their sessions progress, Lucy and Ilse slowly reveal intimate details about their lives. During one visit, Lucy casually settles into a chair that sparks inspiration for Ilse, who asks her to hold the pose—and then requests she pose nude. Initially uncomfortable, Lucy hesitates, but eventually agrees.

Over time, Ilse becomes more entwined with Lucy and Tom, sharing meals and insisting they attend the premiere of her upcoming art show, which will feature a portrait of Lucy. While Tom learns some details about the work, he isn’t fully aware of everything—including a moment between Ilse and Lucy where their professional relationship briefly takes a turn. Without saying too much more, In Transit becomes a poignant story about two women finding new meaning in life through each other.

In her first feature as a writer, Sarrigeorgiou delivers a beautiful, thought-provoking film that smartly avoids painting villains. Instead, she crafts human beings—flawed, searching, and unable to avoid the pain that inevitably crosses their paths. The relationship between Ilse and Lucy feels authentic, not just a convenient plot device. Sarrigeorgiou’s performance makes you feel every flicker of Lucy’s inner life, while Ehle shines in a quiet, reserved turn that hints at the kind of life Lucy might long for.

Visually, the film is stunning. Samantha Tetro’s cinematography offers frames that feel like works of art themselves—lingering shots of Ilse’s studio, the snow-covered New England landscape, and painterly compositions throughout. The imagery is elevated by Juan Pablo Daranas Molina’s beautiful, at times haunting piano score, evoking shades of Eyes Wide Shut. Director Jaclyn Bethany draws us into this world and holds us there until she’s ready to let us go, leaving us to ponder what comes next as the credits roll.

All in all, this tender, female-driven narrative is thought-provoking and deeply honest, with Sarrigeorgiou proving herself a powerful new voice with wonderful things ahead.

For an exclusive discussion with Writer, Producer and Performer Alex Sarrigeorgiou, Director and Producer Jaclyn Bethany, Performer Franço is Arnaud and Producer C.C. Kellogg, click HERE.

Review by Cinephile Mike

*Previously published when screened at the 78th Edinburgh International Film Festival (August 2025).

Love Letters

⭐️⭐️⭐️

Feature Film

Film Production Companies: Apsara Films, Les films de June,

France 2 Cinéma, Canal+ and Ciné+OCS

Rating: NR / Run Time: 96 minutes

Language: French with English Subtitles

Director: Alice Douard

Writer(s): Julie Debiton, Alice Douard and Laurette Polmanss

Starring: Ella Rumpf, Monia Chokri and Noémie Lvovsky

“I can easily imagine you with your daughter.”

In the spring of 2014, in Paris, couple Céline (Rumpf) and Nadia (Chokri) are preparing for the birth of their daughter. As a gay couple, their path to parenthood is far from simple. Under the “Taubira” law, marriage and adoption had become legal for same-sex couples in France, but only Céline is going through the adoption process, while Nadia carries their child via IVF — a method that was still legally restricted for same-sex couples in 2014. This creates a complex and time-sensitive challenge: Céline’s adoption could take anywhere from eight to eighteen months, and Nadia is due to give birth very soon.

Though married, Céline is legally recognized as a third party, and despite taking Céline’s last name, the child would automatically receive Nadia’s maiden name. The adoption process involves photos documenting their life together, statements, a formal hearing, and fifteen letters of recommendation from family and friends. These letters must come not only from other gay couples but from families with children and their own families as well — a requirement that complicates matters for Céline, whose only living parent is her estranged mother, famed concert pianist Marguerite Orgen (Lvovsky). At Nadia’s insistence, Céline seeks out her mother, hoping to bridge the gap and gain a valuable letter for the adoption.

Alongside the legal hurdles, Céline and Nadia navigate the usual fears of first-time parents: finances, preparing a nursery, and questioning whether they are ready. They seek advice from friends and loved ones, even volunteering to babysit for their friends’ children to better understand the responsibilities ahead. Meanwhile, Céline attempts to reconnect with Marguerite, whose temperament is far from mother-of-the-year material, adding emotional tension to the narrative.

In her second feature, Douard crafts an honest, intimate portrait of first-time parenthood. The parallel between the adoption process and the emotional journey of the couple adds depth, offering a narrative rarely explored onscreen. Tender performances by Rumpf and Chokri bring authenticity and heart, making it easy for audiences to empathize with their struggles and root for their success. Cinematographers Jacques Girault and Evgeny Rodin employ a subtle, fly-on-the-wall documentary style, grounding the story and heightening its emotional stakes. Drawing from her own experiences, Douard captures both the joy and anxiety inherent in bringing a child into the world.

All in all, Love Letters is an honest, heartfelt portrayal of first-time parenthood that will strike a chord with audiences.

Review by Cinephile Mike

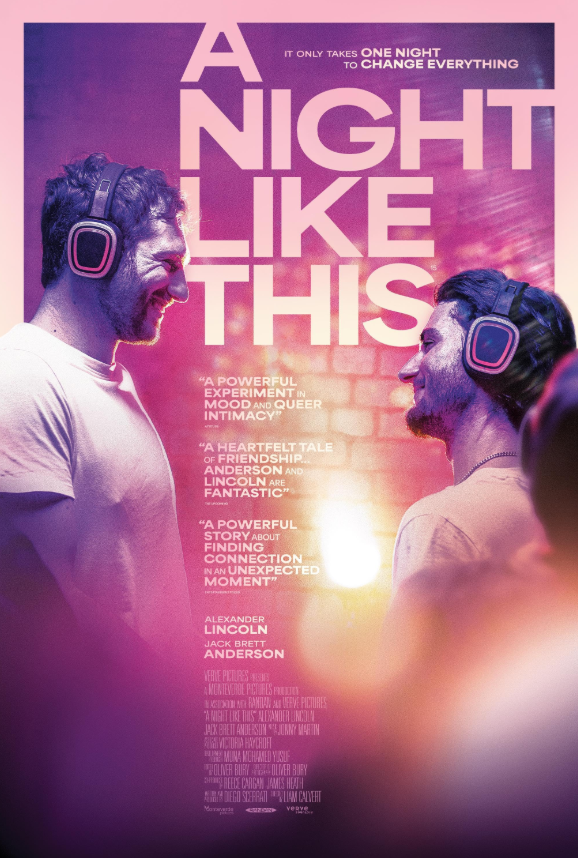

A Night Like This

⭐️⭐️⭐️

Feature Film

Film Production Companies: Monteverde Pictures, Randan, Verve Pictures

Rating: NR / Run Time: 101 minutes

Language: English

Director: Liam Calvert

Writer: Diego Scerrati

Starring: Alexander Lincoln, Jack Brett Anderson, Jimmy Ericson

and David Bradley

“I think sometimes people think they’re better off alone, but maybe

they just run away and hide because they need someone to find them.”

It’s Christmas Eve in London — a time for joy, family, and celebration — except for two lost souls who find each other in a bar. Oliver (Lincoln) is a straight club owner and aspiring musician who can’t seem to stop making mistakes. Lukas (Anderson) is a gay German actor living in London, frustrated by his faltering career and lack of direction, and funds. After a brief introduction at the bar, fate places them on the same bus. Oliver talks a mile a minute while Lukas listens quietly, and though they appear to have little in common, both are searching for connection. When one suggests that it takes two hundred hours for humans to form a bond, they make a pact: spend the night wandering London together and part ways at 8 a.m., when Lukas must head to work.

What follows is a night of small adventures — and smaller revelations. They repeatedly cross paths with a homeless teen, Daniel (Ericson), who’s desperate to stay out of the system. They get into an altercation at a convenience store, stumble into a country music bar on its closing night, and meet its owner, John (a welcome Bradley). Their evening culminates at a silent disco, where the fragile connection between them crosses a boundary they had agreed not to breach.

It’s hard to avoid comparisons to Richard Linklater’s Before Sunrise, which clearly inspires the film’s talkative, time-limited setup. But unlike that film, the chemistry here feels inconsistent. Early on, Lukas’s discomfort is palpable as Oliver barrels through their conversation, and when Lukas suddenly becomes more talkative later, it feels less like character growth and more like a forced narrative pivot. London, meant to serve as a romantic backdrop, never quite comes alive — where Vienna felt like a third character in Linklater’s film, this version of London feels oddly empty, disconnected from the intimacy the story strives for.

Lincoln and Anderson do their best with the material, and there are moments where a genuine connection shines through. Still, much of it feels forced or overly scripted. The supporting characters serve little purpose beyond filling space between stretches of dialogue about regret and failure. Even Bradley, best known as the cranky caretaker Mr. Filch from Harry Potter, delivers a touching scene that nonetheless feels shoehorned in to give Oliver a reason to play music rather than deepen the story.

For their feature debut, director Liam Calvert and writer Diego Scerrati show promise, but their overreliance on coincidence and cliché holds the film back. The intention — to explore the search for human connection — is sincere, but the execution lacks spark. All in all, A Night Like This is exactly that — a fleeting, forgettable night you’ll move past.

Review by Cinephile Mike

Night Stage

⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

Feature Film

Film Production Companies: Avante Films, Vulcana Cinema,

Dark Star Pictures

Rating: NR / Run Time: 117 minutes

Language: Portuguese with English Subtitles

Director(s): Filipe Matzembacher and Marcio Reolon

Writer(s): Filipe Matzembacher and Marcio Reolon

Starring: Gabriel Faryas, Cirillo Luna, Henrique Barreira, Ivo Müller,

Kaya Rodrigues and Gabriela Grecco

“To be the main character, you have to offer what they want.”

Matias (Gabriel Faryas) is driven—he wants to be a star, no matter who gets in his way. He’s preparing to make his debut in a new theatrical show alongside his friend and roommate Fabio (Barreira), and excitement fills the air: a casting director will be in attendance, with her eye on Fabio for a role in a major national television production. Matias is jealous, but channels that energy elsewhere—cruising parks, swiping through dating apps, and indulging in risky encounters. One night, he meets “Discreet,” a mysterious stranger named Rafael (Luna), who takes him to the outskirts of town for a tryst that blurs the line between secrecy and danger. Despite Rafael’s warning that he “doesn’t do second dates,” something undeniable sparks between them.

But secrets run deep. Rafael, it turns out, is a prominent political figure—one backed by powerful men as he prepares to run for mayor of Porto Alegre, the Brazilian city that serves as the film’s backdrop. His bodyguard, Camilo (Müller), keeps watch over both his safety and his secrets. Meanwhile, Matias, caught between ambition and obsession, makes his own ruthless move—sabotaging Fabio during a critical performance and stealing the role that could have made Fabio a star. As Matias’ career rises and his affair with Rafael intensifies, their entanglement threatens to consume them both. In a world where visibility is everything, desire can be the most dangerous exposure of all.

In their third feature film, Filipe Matzembacher and Marcio Reolon craft a slick neo-noir erotic thriller in the spirit of old-school Verhoeven and De Palma. The film’s tension doesn’t hinge on the fact that its leads are gay—it’s about the politics of image, the price of pleasure, and what happens when private urges collide with public life. The writing is sharp, the pacing taut, and the moral terrain deliciously gray.

Faryas, in a commanding debut, gives us a protagonist you can’t decide whether to despise or admire, while Luna’s Rafael hides an entire double life behind his politician’s smile. Cinematographer Luciana Baseggio captures Porto Alegre in hypnotic, neon-drenched tones, set against a pulsing score by Arthur Decloedt, Thiago Pethit, and Charles Tixier. It all builds toward a jaw-dropping finale that lingers long after the credits.

All in all, Matzembacher and Reolon deliver a visually stunning erotic thriller that dives deep into desire, ambition, and public scrutiny—and dares you to look closer at what we want, what we hide, and what happens when the two collide.

Review by Cinephile Mike

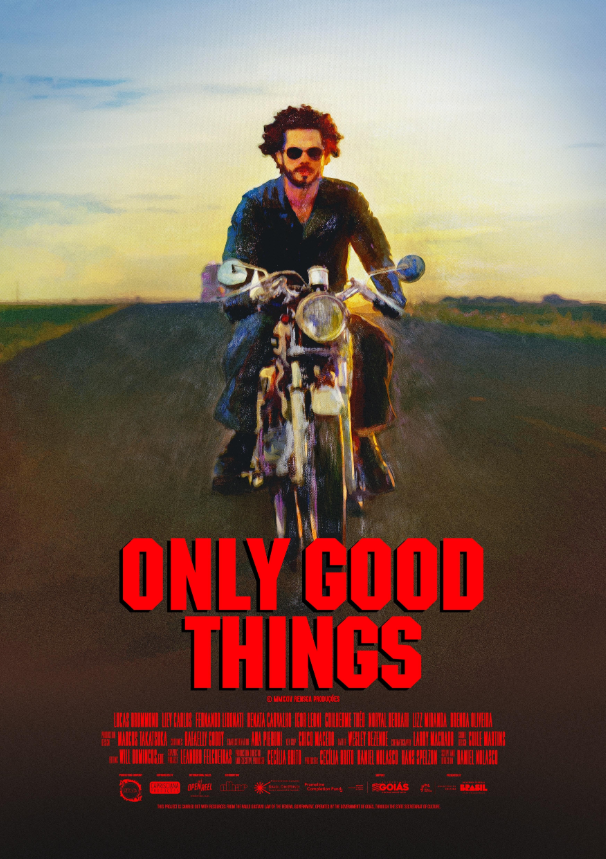

Only Good Things

⭐️⭐️⭐️

Feature Film

Film Production Companies: Rensga Produções and Caprisciana

Produções

Rating: NR / Run Time: 104 minutes

Language: Portuguese

Director: Daniel Nolasco

Writer: Daniel Nolasco

Starring: Lucas Drummond, Liev Carlos, Guilherme Théo, Norval Berbari,

Fernando Libonait, Igor Leoni and Renata Carvalho

“You’re old. Sick. If you live for a few more years, it would be pure luck. I don’t need to kill you, sir. Because you, your blood, your inheritance, your future die with me. It will end with me.”

Only Good Things opens in the Brazilian countryside in 1984, where we meet Marcelo (Carlos), a man on a journey — though we’re never quite sure of its purpose. Riding his motorcycle across the rural region of Batalha dos Neves, Marcelo crashes and is left injured in the middle of the road. Nearby, Antônio (Drummond) struggles to keep his small farm afloat while fending off persistent pressure from Samuel (Théo), his father’s associate, who repeatedly urges him to sell and move on. Antônio refuses, and tension simmers between him and his father Tavares (Berbari), whose secrets loom over the story.

Through a fateful encounter, Antônio discovers the wounded Marcelo and brings him home to recover. Details of Marcelo’s past remain vague, but almost as soon as he arrives, the two men fall into a passionate relationship — one that’s depicted more graphically than expected, pushing into NC-17 territory (though the film remains unrated). As their bond deepens, it sparks conflict among those around them, ultimately escalating to tragedy. Just as the story reaches a boiling point, the film abruptly jumps to present-day Brazil.

Now, Antônio (played by Libonati) lives comfortably in a modern apartment, haunted by memories of Marcelo, who seems to have vanished from his life. He spends his days staring at an old photograph of their younger selves, fending off flirtations from his assistant Eduardo (Leoni) and silent judgment from his housekeeper Helga (Carvalho). What follows is a meditation on love lost and time’s cruel erasure — though one that feels more like a narrative reset than a continuation.

Here’s the frustrating part: Only Good Things feels like two separate films spliced together, and neither receives the conclusion it deserves. Is this meant to be a sweeping romance spanning decades, or a surreal multiverse fable about two men forever bound by fate? Nolasco never quite decides. The first story, set in 1980s Brazil, is easily the stronger half — anchored by the smoldering chemistry between Drummond and Carlos. Drummond delivers a gripping performance, exuding intensity whether confronting his domineering father or surrendering to forbidden desire. Carlos plays the more restrained counterpoint, his quiet presence igniting Antônio’s passion. By contrast, the present-day storyline feels disjointed, shifting from a tender rural romance reminiscent of Ang Lee’s Brokeback Mountain to a fragmented noir akin to George Sluizer’s The Vanishing.

In his fourth feature, writer/director Daniel Nolasco clearly has ambition — and something to say — but the film’s split structure and tonal shift work against him. His writing is sharp, his performers game, and Larry Machado’s cinematography beautifully captures the Brazilian landscape. Yet once the story moves from open fields to city apartments, the film loses its emotional oxygen. All in all, Only Good Things struggles to find a cohesive narrative voice, leaving us yearning for the stronger, more focused film — or films — it could have been.

Review by Cinephile Mike